Koak interview

Flavio Affonso

I think your drawings speaks by themselves, but I would like to know the person behind those drawings. How would you describe the path from comics to your current work?

I don’t think it’s necessarily that I’ve come to my current work from comics—fine art and comics have equally been a part of my practice since I started making work publicly as a teen.

To me, the two things—exhibitions/fine art and comics—share a very synonymous language.

Many of the same forms of articulation or modes of conveying information can be applied to both. At their most basic level, they are both dependent on how the eye follows a narrative across space—be it the page of a comic, the surface of a painting, or a physical installation.

Both of these practices will always be a part of my life–they will continue to inform one another, and their presence in culture around me, both historically and contemporarily, will continue to influence my practice.

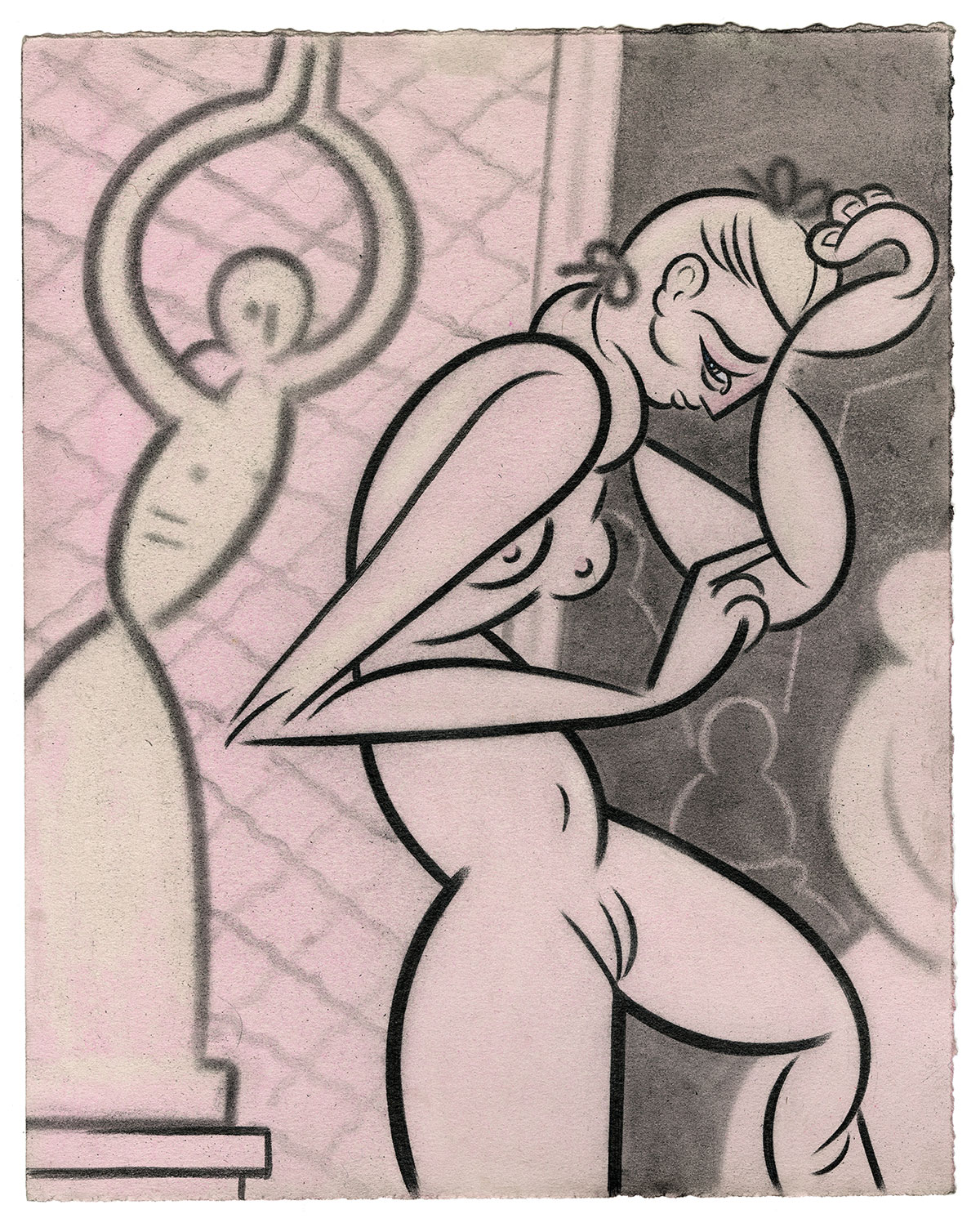

I find opposites in your drawings: dark/shining colours, naked/not erotic, suffer/abstracts, Am I wrong? Or what can you say about this opposites?

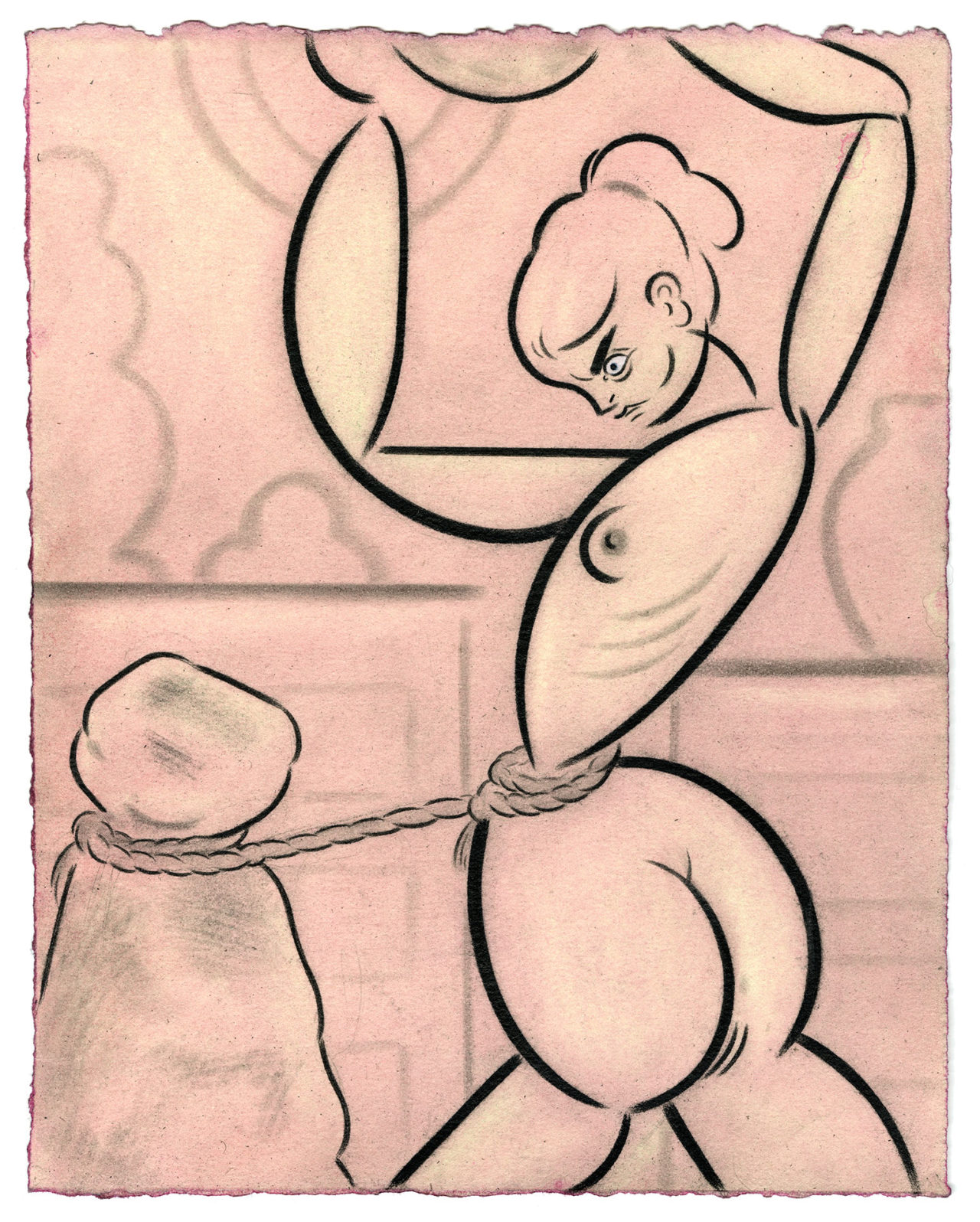

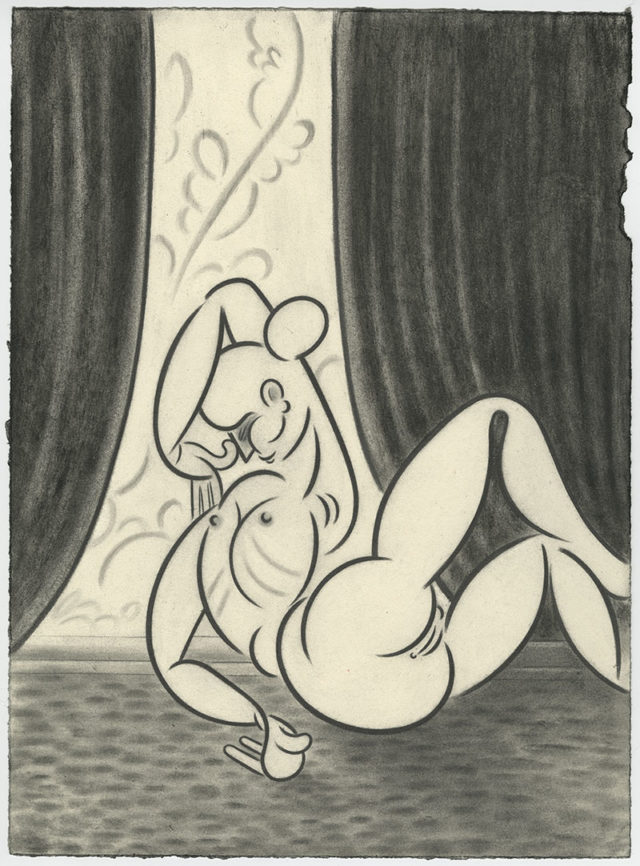

Opposition plays a very large part of my work. I am always interested in creating moments of tension, because those little conflicts in an image are what bring a sense of life to the work. Paintings—like a good novel, film, or song—are made dynamic and compelling through tension. It’s duality, tension, and conflict that drive the story forward, create mystery, or add the depth of perspective.

It is also very important to me—especially now as an artist living and working in the current hyper-polarized political climate of the US—to strive to make work that exists in the spaces beyond extreme polarities. There is nothing in this world, as far as I know, that exists simply or just as it’s seen, so it is very important for me to create work that reflects that sort of complexity, that goes beyond the surface extremities. Even if the work I’m making just contains a single figure, ensuring that figure has a sense internal opposition is an essential element to my process.

How did you started drawing? At what age?

Art was always something that was present in my life, even as a very young child. My family was very supportive. Both of my parents played music and my mother always encouraged me to draw. When I was a teen, it became a more regular, and public, aspect of my life. I started making comics at around 15 years old and showing my paintings at local coffee shops and dive bars. There was a certain aspect of complication to my teenage years, and making art was the lifeline that I needed to communicate and connect to others.

What did you find in the formal education?

I think the biggest transformation I had was learning how to not close myself off to the amazing wealth of artwork we have available to us at the moment.

There is a tendency that I think a lot of artists have, where, when you are still in the process of forming your own voice, you shut down to taking anything new in. You don’t want to look at work you don’t like because you are judgmental of it, and you don’t want to look at the work you aspire to, because, quite honestly, it’s physically painful.

That changed for me when I got my undergrad. I pulled out of myself and started looking at work that challenged my view point of what art was. I let myself be uncomfortable. It became important to be very open about what others’ conception of art was, what “good” was, and to look at everything with the intention of how I could learn from it.

Do you have a work routine? Where does the drawings are born?

I think my work routine is to always work, which is something I’ve been slowly trying to dismantle. The last two years have been very busy, which has been wonderful in the sense that I love to work, but also very destructive to the ideal of living.

I’m woken up by the thoughts of everything that I feel I need to do during the day. There is generally a sense of urgency to everything that, in my heart, I know isn’t really urgent in the scope of life.

Maybe this is myself being overly honest, but it is an aspect of living in a world that feels as if it moves faster than you are able to breathe. I jump straight into working—whether that’s means going to the studio, where I work on larger pieces, generally with an assistant, or from home, where I work on smaller drawings and I am able to spend time with my cat and partner.

In a way the concept of having a work routine, to me, is an irrelevant thing. Routines are flexible ideas that mold themselves to your deadlines—they are driven by the urgency of vision and time.

What feelings are present when you draw?

Whatever the piece I’m working on asks for. So much of the work is about bringing emotions to life in the work, so it’s very important for me to kindle an emotional resonance with the intention of the piece—to create a spark of the feelings that are needed by the work, and then to give them over to the page, or the canvas, or the clay.

What are you looking for in the espectator?

A human.

What can you tell me about your influences, music, books, movies, ordinary life?

I’ve been listening repeatedly to Brian Eno’s song Dead Finks Don’t Talk from his album Here Come the Warm Jets. There is something about it that feels like the musical version of what I desire from art exhibitions.

Here’s this song with so many parts that feel disparate, almost like characters in a play, each with their own accompanying musical sets…But everything, all these different tones, come together to make something that is lush and incomparable. I think that it is the perfect song for what I would hope an exhibition to be, especially during this moment in time, when so much of the art being made is a collage of elements from the past, a remix of history.

I am influenced by a lot of things, but at the moment, that is what I’ve been inspired by the most.

How did you find this line, this kind of expression?

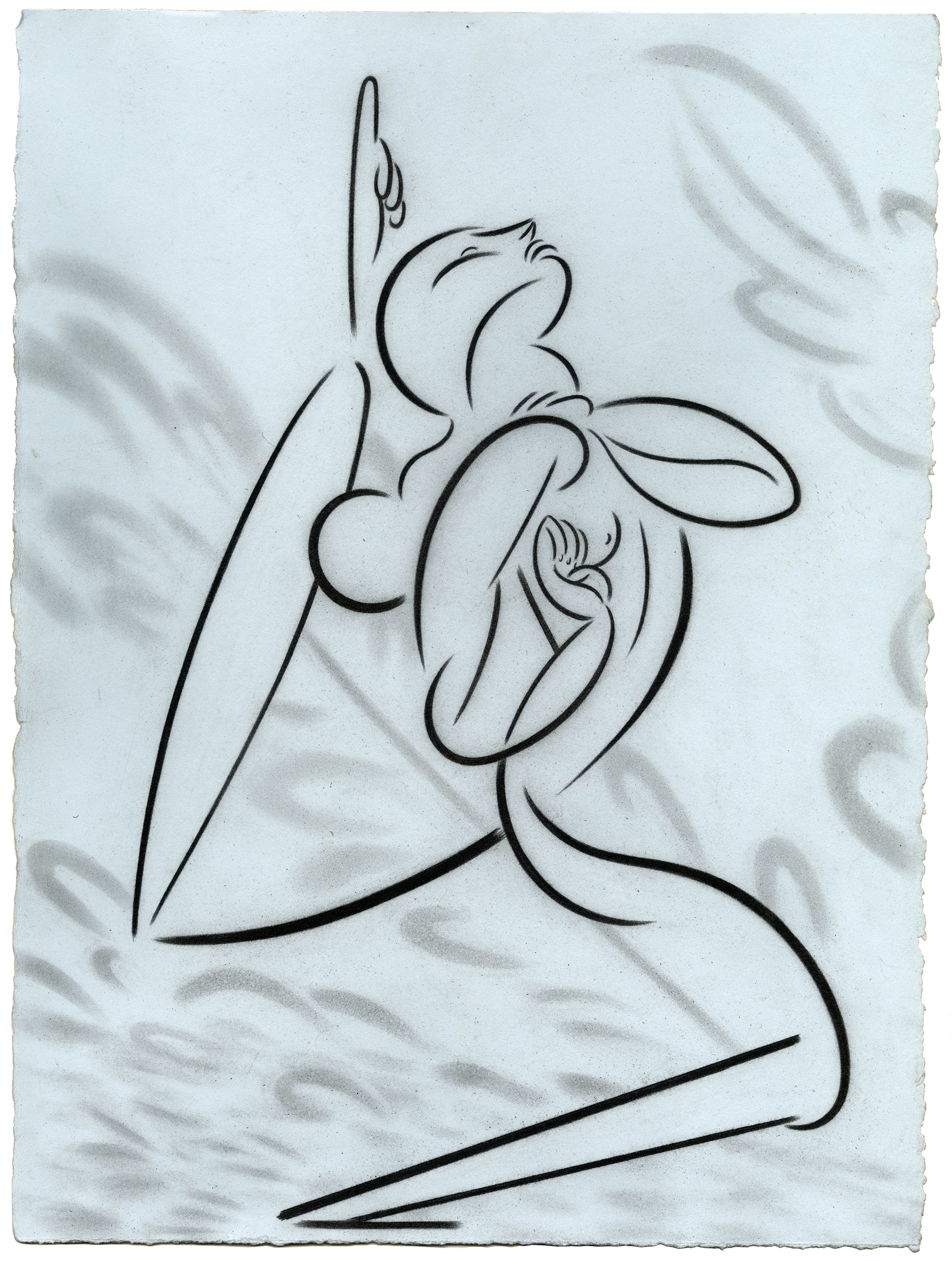

A line is a very powerful tool. It is the simplest of things, yet can be used to convey all the intensity of life that language cannot contain. Any sort of flex or bend in its curve, any change in the tone of how it’s applied (wavering, bold, hesitant), will change its expression and the resulting emotion in how we experience it.

Because my work is about communication—and communication very often needs to be clear yet nuanced—the line must be the champion of my work. It is always the thing that I put first in order to push the narrative forward.

What are you working on now?

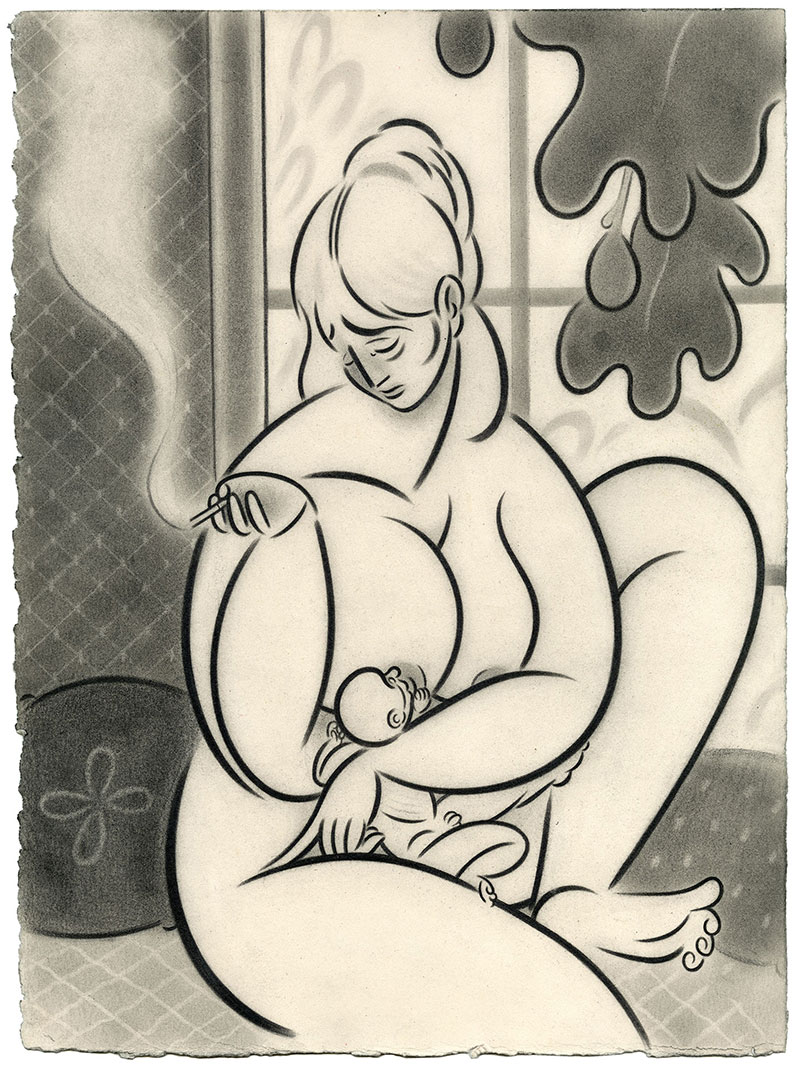

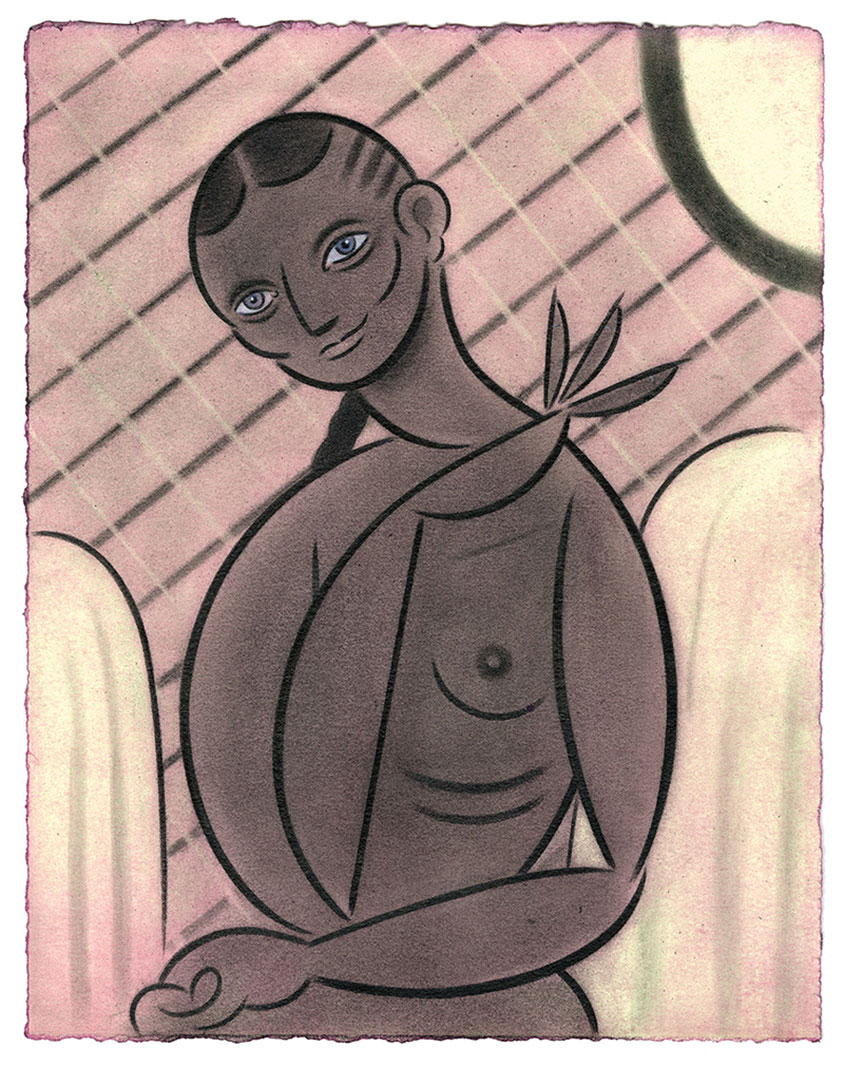

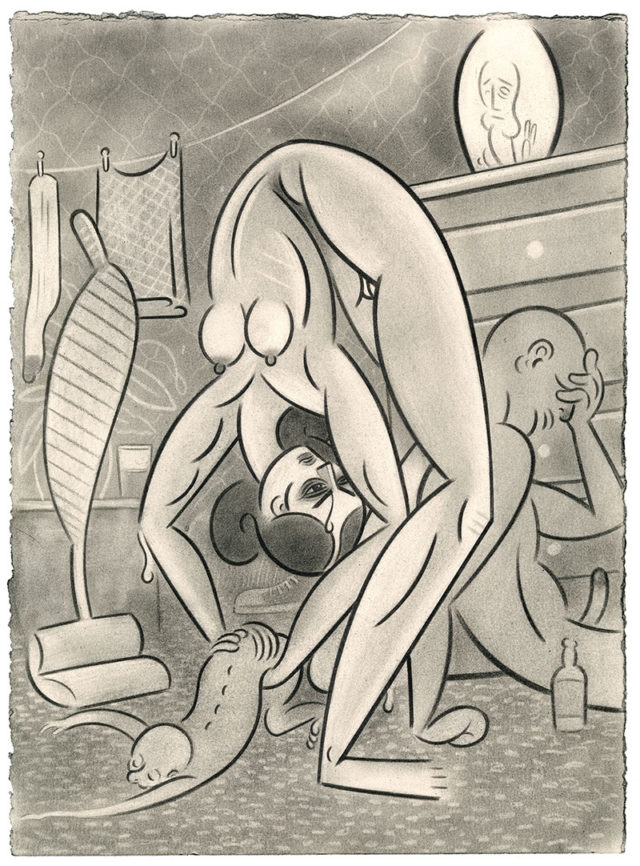

Right now I’ve just finished up a body of work for a solo show at Walden gallery in Buenos Aires, which will be running until June 19th. The series, called Seed For Planting, is based on a quote by Kathe Kollwitz; “The seed for planting must not be ground.” Kollwitz’s quote refers directly to losing her son who fought in World War I; in it she refers to him as the sowing and her the cultivator.

I’ve thought a lot about this quote in life—not only as how it pertains to mothers and caregivers—but also how it pertains to women as creators. I don’t know what it’s like to be a man making art, but I know from my own experience, and from communicating with women around me, that the process of making art for many women is one of cultivation. There is something in it that requires growing a life, and then putting that life out into the world and trusting that it will exist on its own–that it will find a path beyond you, have its own sense of existence, and continue to grow beyond your hopes.

To me, her quote speaks to the fact that we cannot destroy what is needed for the future in order to survive the present. The work in the show focuses on women as both maternal and artistic creators, as well as the sometimes tumultuous path of navigating how to survive and sustain through the more trying aspects of those livelihoods.

What do you think about the welcome the art industry has received your work with?

I think as an artist, there is always some intention behind how we want our work to be perceived. For me, it is most important that the work communicates with people, that there is some form of resonance with them. I would make the work regardless—there is always that need to keep creating—but at the same time I don’t make the work for myself. It is very much an undertaking with the intention of communication with others at its heart.

In that way I feel very thankful. Somehow, in moments of isolation within my studio, I’ve been able to make work that people with very different lives than my own can connect to. I don’t want to say that in a way that sounds as if I’m bragging or naive; it’s what I strive to do. So I’m very happy that it has happened, but it also really illustrates the power of art to me—why it is such a vital and irreplaceable aspect of human culture and communication.